If the westernmost Colorado River draining seven states is sometimes called “America’s Nile,” its smaller namesake river draining Central West Texas through Austin might be dubbed “America’s Tigris.”

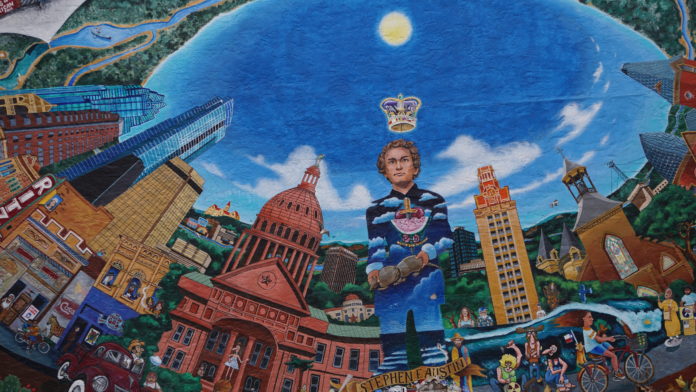

For the ambitions over the last century and a half to build a green and urban paradise, by channeling and engineering the Texas Colorado’s flow, invite comparison with those of the 6th Century B.C. king who created the mythical Hanging Gardens of Babylon along the Tigris in today’s Iraq.

As with the Tigris that nurtured some of humanity’s earliest settlement, it was Austin’s river that seeded the city’s founding. Over countless millennia, the Colorado River cut through the Hill Country to carve the meandering canyons of layered limestone. In turn, this sculpting created the unique environment at the edge of the Balcones Escarpment, where the Edwards Plateau grows west from the Gulf Coastal Plains to the east.

It was the river that drew the earliest settlers here and it was the artery that was to make the city a new nation’s capital in 1839, six years before Texas joined the United States. Ever since, Austin has been remaking the river that birthed and nurtured it – creating an engineered landscape that would probably make an ancient Babylonian King proud.

The series of six dams and reservoirs that were to ultimately staircase up behind Austin were to become the catalyst behind the city’s first plan in the late 1940s to woo knowledge workers and build an economy on technology, or “electronics” in the term of the era. From the top of the staircase downward, the Highland Lakes are Buchanan, Inks, LBJ, Marble Falls, Travis and Austin.

The waterfront mansions that line the shores of Lake Austin, and further up lakes Marble Falls and LBJ, are among the creations of Texas’ Babylon. Unlike with the two largest reservoirs Buchanan and Travis, the high-end development of multi-million dollar homes was possible as these are so-called “constant level” or “pass-though” lakes whose shorelines don’t ebb and flow. Although that may be changing as development in the watershed cuts inflows, build-up of sediment shrinks overall reservoir capacity and dramatic sand accumulation clogs the idyllic, fjord-like tributaries.

Some $250 million in annual tourism revenue undergirds the local economy. Although lakefront property is less than 2 percent of the geography of the surrounding two counties, it represents 47 percent of the regional property tax base.

Today, the dams’ operator, the quasi-state Lower Colorado River Authority, or LCRA, provides virtually all the municipal water to Austin and a dozen other Hill Country cities as well as flood control, irrigation and electricity.

“A dam is more than a collection of concrete and steel,” then-Sen. Lyndon Johnson said in a 1957 speech at Lake Buchanan that captured the political and cultural ethos toward the river since the time of Stephen Austin. “It is also a human achievement of the highest order.”

Achievements and unforeseen new challenges

It’s a noble sentiment. And the achievements are unquestionably many. The floods were tamed and the impact of droughts eased. Less recalled today was the potential of electricity that pulled the creation of the LCRA through the politics of the Depression and won the $60 million in federal funds that ultimately flowed to the engineering of the river. In those years, only 2 percent of rural Texas had electricity.

But at the time, the provision of drinking water – as opposed to irrigation to farms — was at best an afterthought. Austin had been drawing water from the Colorado since the 19th Century and opened its first water treatment plant in 1925, roughly where the Central Library stands today. And Austin was to make a deal with the LCRA for water from Lake Austin once it was filled in 1940. But with Austin’s population at less than 50,000, and the hamlets surrounding the lake little more than cross roads, household water supplies were a low priority. In fact, when Austin bought Barton Springs in 1916 the intent was its use as a reserve water supply. But the city didn’t need it. Which is how and why it became today’s treasured parkland, with a swimming pool the size of two football fields.

Today’s operating logic is quite different than that envisioned by Johnson and other pioneers, including Walter E. Long, the longtime civic activist credited by many as the LCRA’s true intellectual father. For today, the power generated by the LCRA’s dams is no more than 2 percent of the total, as most energy comes from a network of five coal and gas fired plants including one co-owned with Austin’s energy utility. The energy produced independently of the dams’ hydro generation capacity now provides more than 90 percent of the LCRA’s $1 billion-plus revenue.

That afterthought of water 80-plus years ago, however, has meanwhile become the lifeblood of Central Texas and the object of urban desire throughout a region set to soon become North America’s 11th “Megaregion,” a conurbation surrounding Austin that will have the population of greater New York City in less than a decade. By 2030, the so-called “Texas Triangle,” bounded by Dallas-Fort Worth in the north, Houston on the south, San Antonio on its western edge and Austin at the center, will grow by 20 percent to a population of 20 million.

The font in the middle of thirsty Central Texas

Where will the current population and the 4 million newcomers get their water? Or where will the 15 million newcomers expected by 2050 do the same? There is no bigger unanswered question before the region’s planners. But the font in the middle of it all is this Texas Babylon.

Today, that Babylon yields 411,000 square feet of water in so-called “firm” or guaranteed contracts to 150 customers. For perspective, that much water is enough to cover the entire city of Austin’s 298 square miles a little more than two feet deep. And each year, Austin has claim to 35 percent of it all, locked up in a 1999 contract good through 2050. The LCRA also waters 11 other cities, several dozen local utilities and 15 resorts and golf courses. And while the authority generates no nuclear power directly, roughly 10 percent of that contracted water provides the cooling for the South Texas Project, the state’s only nuclear generator located near Matagorda Bay and in which Austin owns 16 percent.

Contracts for water above that amount are essentially “as available,” subject to the weather cycle. A dizzyingly complex set of legal arrangements and formulae govern the allocations to four irrigation districts downstream of Austin to the Gulf that, while far more subject to capricious weather and water availability, enable a cotton and rice-growing economy worth more than $300 million annually.

So while the garden cities of Austin and those above in the Hill Country don’t quite hang in the image of Babylon, they do represent a unique urban and suburban terrace in an otherwise arid region. It’s a waterscape that totals seven lakes when considered with Lady Bird Johnson Lake, created in 1960 with the Longhorn Dam built by the city of Austin.

All of this massive infrastructure is the product of the massive-scale $2 billion spate of dam building undertaken by the Depression-era New Deal’s Public Works Administration, run by the Department of the Interior. The epic scope of that dam building, equal to $36 billion in 2019, literally changed the face of America’s West and Southwest. Hoover Dam on the western Colorado. Grand Coulee and Bonneville dams on the Colombia River in Washington State. The Shasta, Friant and 18 other dams that now encircle California’s Central Valley. To name just a few.

Capturing the water of the Texas Colorado, however, was hardly a sudden federal decision. For efforts to harness the sustenance and power of the Texas’ 860-mile long river are older than the state itself.

In the beginning

For millennia, the native peoples of Texas were drawn to both the river and the artesian springs north and south of it fed by the Edwards Aquifer which shares its watershed with the Colorado in Central Texas. That aquifer, of a decayed and highly porous limestone known as karst, is the source perhaps most famously of today’s Barton Springs and also Comal Springs near New Braunfels. The latter is America’s largest freshwater spring west of the Mississippi.

The well-known Spanish explorers were similarly drawn. And as early as 1828, the colonizer of what was to become Anglo Texas, Stephen Austin, noted in a promotion pamphlet that the Colorado “affords great facilities for water works and irrigation.” A decade later, the Texas Republic’s first president, Mirabeau Lamar, appointed a commission to recommend a suitable capital city. Its conclusion that “…the great desirderatums of health, fine water, stone, stone coal, water power etc, being more abundant on the Colorado” than in any alternative sealed the deal for the capital. Almost immediately upon its 1839 founding, Austin’s civic concerns were led by flood control and hopes to make the Colorado River navigable and build a dam.

A side wheel steamer, the Kate Ward, was assembled in La Grange and made it upstream to Austin in 1846, a year after statehood. Efforts to navigate all the way to the Gulf via Matagorda Bay were thwarted by the perennial problem of massive driftwood logjams at the mouth until an 1848 flood cleared a path and the Kate Ward finally made it to open water. She then plied the Guadalupe River until lost in a hurricane in 1854.

Further attempts at navigation were tempered first by the Civil War, and later by the arrival of railroad service to Austin in 1871. But within a decade, the imperative of a dam reemerged and by 1890 construction, financed by the city, began. Lake McDonald – named for the era’s mayor John McDonald – was full by 1893. It was the first major reservoir in Texas.

While it’s a bit hard to imagine today, before the turn of the 20th Century Austin residents could board the triple-decked, side-wheel steamship Ben Hur just west of today’s downtown and travel 30 miles upstream on Lake McDonald. This earlier version of Lake Austin was eight miles longer than today’s, allowing the Ben Hur and another steamer, the Belle, to run regularly scheduled service to roughly a point that is now the city of Lakeway.

An international regatta was held in 1893 on Lake McDonald where Australian rower James Stanbury set a world record for sculling. Power from the 60-foot dam, near where Red Bud Isle Park is today, made Austin one of the first cities in America with an electric street car system and public lighting. A housing boom ensued amid it all, foreshadowing the city’s growth pains so familiar today. Developers led the boom on the northern fringe with promotion of a new “streetcar suburb.” They named it Hyde Park.

It wasn’t to last, this early effort to remake Austin’s environment. On April 7, 1900, as floodwater cascaded 11 feet over the dam, it suddenly gave way, killing 47 people, flooding much of downtown and draining the lake behind it.

“The wrecked dam sat derelict, ‘a tombstone on the river’,” wrote University of Texas at Austin historian Bruce J. Hunt in one account. And despite many efforts and more flood devastation, it was to remain pretty much a tombstone for the next four decades as Austin hitched horses to its street cars and kerosene again became the main source of light.

“It was the era of frustration,” remembered Long, the civic activist who led the creation of the LCRA’s predecessor entity, the “Colorado River Navigation Congress,” in 1915. A year later, it was reorganized as the “Colorado River Improvement Association,” a project that led not just to the LCRA, Long wrote in his 1956 book From Flood to Faucets, but a “movement… to conserve and utilize properly every drop of flood water in Texas.”

Just seven years after that first dam’s collapse, which burdened the city with $1.3 million in remaining debt, enthusiasm for work on the waterway resumed.

Upstream a dam was attempted in 1908 at Marble Falls, only to be abandoned a third complete. Austin commissioned a replacement for its city dam in 1911 only to see it damaged before completion and destroyed in 1915 with the further loss of 60 lives. And yet another privately-funded dam effort was begun where today’s Buchanan Dam tops the High Lakes. That too was left incomplete after bankrupting the developer.

Toward a publicly owned dam on the Colorado

The sum of that sentiment was the Texas decision to take no more chances on private dam-building ventures, overcoming however briefly the state’s wariness of government-led initiative. In 1934, the state legislature created the LCRA.

The massive reengineering of the waterway through the Hill Country canyons was not to advance without ceaseless opposition by interests from the river’s headwaters south of Lubbock to its mouth at Matagorda Bay. Texas lawmakers fought bitterly with the funder, the U.S. Department of the Interior over dam height and scope. And lawsuits by private utilities challenging the constitutionality of publicly funded power projects went all the way to the Supreme Court. The need to insulate the LCRA from the legal threats in particular were among the reasons the agency was vested with unique autonomy and exclusive control of the dams and reservoirs. Today, the LCRA is one of the few major dam projects in the United States, and the only one in Texas, that is not operated jointly with the federal Bureau of Reclamation or the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

And so this new entity, now ultimately almost a century old, was to at last realize the vision to yoke Austin’s future to the now familiar waterscape built from the Colorado River: the six-dam, hydrological staircase backing deep into the Hill Country.

“In less than a decade, during the New Deal, Central Texas initiative with federal government assistance, was able to control and develop the Colorado River,” wrote historian John A. Adams Jr. in Damming the Colorado, a 1990 history of the LCRA. “Centuries of vast seasonal flood damage were eliminated and exchanged for a well-managed system of dams, reservoirs, and hydroelectric power stations.”

Or were they?

The next century is sure to bring even more volatile weather to Texas than the last. Climate scientists say future droughts could last decades rather than just years. New problems and flagging capacity stalk the LCRA operations today. And there are no new dams to build. Which is why Austin and other Texas cities are moving to design a water future that will not remotely resemble the past. It is a future unfolding amid skyrocketing regional growth that will rely far more on conservation, radical water reuse and technologies never even imagined by the dam builders of the Texas Colorado.

Editor’s note: This article is edited and adapted from a monograph published in the January Water Issue of Urbānitūs.

If you like what you’ve been reading, please click here to subscribe and we will send you updates and our newsletter.