Among those living in Austin since the turn of the century, one is constantly confronted by the bracing reality of gentrification. It is, so the consensus goes, the unfortunate side effect of the growth that our city has been blessed with. Austin, that blue dot in a red state, Brooklyn in the heart of Texas, Groover’s Paradise, the Live Music Capital of the Word…. Who wouldn’t want to move here?

As California’s cities become too expensive for a young family to buy a home without a “small loan” from their parents and the average New Yorker spending the equivalent of a full work day each week commuting, it doesn’t take a lot of imagination to understand how a once quaint college town on the edge of Texas’s hill country, where you could own a house with a boat dock a 10-minute drive from downtown for less money than a 3/2 in Greenwich Village, has become the fastest growing city in the country.

Cities lack the sovereignty of national or state governments. This is a fact that Austin has proven time and again with its battles against the federal government around immigration and the state government over issues ranging from restrictions on ride-hailing services to the current decriminalization of homelessness. But just because a city may lack the autonomy to effectively execute its goals, doesn’t negate the fact that it does not have them, even if they are not fully articulated. And in Austin, like in most major cities in the US, that goal, however subliminal it might be, may as well be a play on quote from Gordon Gekko, the fictional character in the 1987 film Wall Street: “Growth is good.”

That is not to say growth is not beneficial. It’s not to weigh in on the debate of whether Austin should have been bidding on Amazon’s second headquarters or whether the presence of Apple, Google, and Facebook are good for the city. It’s not a stance on the pro- vs. anti-density factions that define the city’s politics or a comment on whether a new soccer stadium or affordable housing is a better use of city-owned land.

It is just a statement that Austin has been proud of its rise. While residents may complain about the increased traffic or sky rocketing home prices, the city touts itself as a new technology center, boasts about its burgeoning tourism, views its inbound migration as a reflection of its greatness, and generally basks in its newfound spotlight. And it has grown in a fashion that makes its now walkable downtown a stark contrast to the nearby commuter metropolises of Houston and Dallas, where a car is a prerequisite to survival.

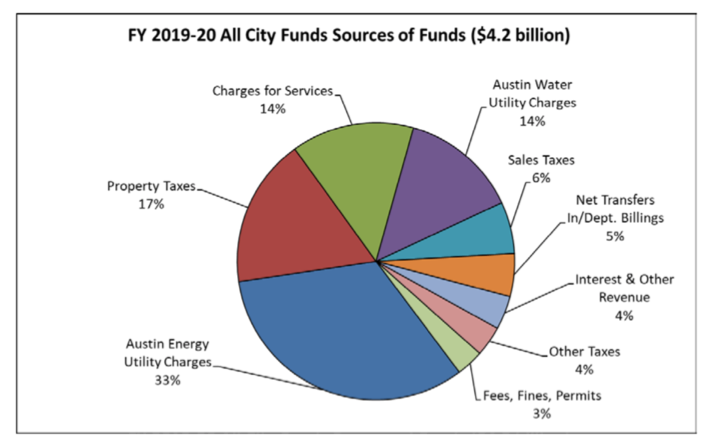

But such things cost money and while Austin has many revenue sources, the reality is that once the direct costs of operating city services, like Austin Energy and Austin Water, are factored out, property taxes and sales taxes make up three-fourths of Austin’s General Revenue Fund, with property tax representing half of the fund.

In a statement that any physicist (and most economists) would appreciate: if the goal is to maximize taxable property value, then gentrification isn’t an unfortunate side-effect, it is literally the stated intention. That is the fundamental premise of Samuel Stein’s “Capital City. Gentrification and the Real Estate State.” Increasing property value is, by definition, replacing low value properties with higher value ones, or as one may less politely state: gentrification.

That is not to say that Stein does not have his political leanings. But for all the noise that can be found around local politics, this simple, but poignant, truth is as close to a law of nature as one could imagine. Just as the leftward leanings of Robert Oppenheimer did not make the atomic bomb any less explosive, neither does Stein’s discredit the inherent contradiction between increasing aggregate city-wide property values and preventing gentrification.

The fact is that the city council, the mayor, the city planners, and all city employees receive 50 cents on every dollar of their paycheck from property taxes. All the initiatives that the city government needs to fund are paid for in large part by property taxes. So it’s natural that this is a, if not the, goal of city planning.

In fact, the first line of text on City of Austin 2020 Budget, and the only introductory text to the 843-page budget is:

“This budget will raise more revenue from property taxes than last year’s budget by an amount of $64,091,204, which is a 9.5 percent increase from last year’s budget. The property tax revenue to be raised from new property added to the tax roll this year is $15,097,747.”

Without a hint of irony, in the opening letter to introduce this same budget, City Manager Spencer Cronk cited the need to raise additional funds to achieve the “Council’s top two strategic priorities of affordable housing and homelessness.”

Due to state restrictions that prevent material increases to tax rates, the only way to raise property tax revenue is to increase the taxable base. There are two tools to do this: reassess existing properties at a higher valuation or build. Or better yet from the city’s apparent perspective, both. Reassessment has been happening as quickly as can be managed. There is a new city-wide reappraisal process underway that has gone as far as a drift into legal grey areas with the questionable use of data from private real estate data sources of MLS and CoStar. Not to mention the cancellation of Travis County’s formerly informal protest hearings that gave the layperson a chance to state his or her case. The civic backlash around increased valuations on existing properties, and the fact that the appraisal process technically falls outside of the city’s jurisdiction and is controlled by Travis County Appraisal District (TCAD), results in a focus on new construction.

The 2020 budget “represents an increase of 8.8% over last year’s valuation. New property value is projected at $3.4 billion and is primarily driven by the construction of residential, multi-family, and commercial properties.”

New construction needs to replace something and while we can create new buildings, we simply cannot create new land. When we are talking about building in a downtown such as Austin where cranes currently blanket the horizon, that something is increasingly low-valued property ranging from under-sized commercial properties to single family homes; the properties whose replacement yield the largest increase in value. The downtown is more walkable and vibrant than it was at the turn of the century when it was less dense and open air parking lots filled the spaces now occupied by skyscrapers. But it is simultaneously less accessible to local businesses, renters, low-income families, and minorities.

Stein reflects that “neoconservative planners starved their cities; neoliberal planners begged capitalists to feed off them.” No one would accuse the current Austin city government of a conservative bias. In many regards, it’s been an incredibly liberal, activist government that has made a stand against a conservative state government headquartered in its own city.

But one must ask how much of that focus is on solving problems that it itself has created, albeit with far more effectiveness than its ability to solve them.

If you like what you’ve been reading, please click here to subscribe and we will send you updates and our newsletter.

Generally I don’t learn article on blogs, but I wish to say that this write-up very pressured me to try and do so! Your writing style has been surprised me. Thank you, very great post.| а

Howdy I am so glad I found your blog, I really found you by accident, while I was researching

on Askjeeve for something else, Anyhow I am here now and would just like to

say thank you for a incredible post and a all round

enjoyable blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time

to go through it all at the minute but I have bookmarked it and also added your RSS feeds,

so when I have time I will be back to read much more, Please do keep up the awesome work.