Editor’s note: In light of America’s nail-biting election now down to the tedious count of ballots in the upper Midwest, we are republishing this review of the insightful 2016 book which looked at the stark political divide in Wisconsin, The Politics of Resentment by Katherine J. Cramer. Just as the analysis of Cramer’s book has stood the test of time, her work now stands as a masterful critique of the future in an America that this week’s election has defined as mercilessly divided into opposing realities.

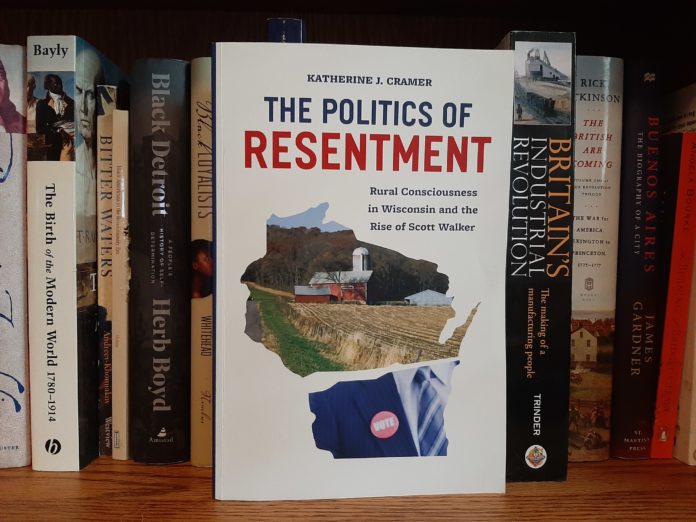

Review: The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker, by Katherine J. Cramer, 2016, 281 pp., University of Chicago Press

With just over sixty days between now and the most consequential election of our lives, there is no shortage of commentary on the fact that the decision will not really be made at the national level. Instead, a handful of closely contested battleground states, mainly in the Upper Midwest, are likely to determine the course of our national future.

Three of these states were seen as safe for Hillary Clinton on election night 2016. But Donald Trump flipped all by narrow margins, defying the wisdom of pundits and seasoned statistical modelers – in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

These states represent perhaps the most acute microcosms of the political divide facing our country from coast to coast. But Wisconsin, nestled between two Great Lakes and representing just 10 electoral votes, might be the most highly competitive and deserving of the most attention. It contains areas that most greatly underperformed Democrat expectations, and might represent President Trump’s key to hanging on to the Oval Office.

One of the most enduring critiques of the Clinton campaign is that she paid little to no direct attention to Wisconsin, becoming the first candidate from either major party to skip a Wisconsin visit since Republican Richard Nixon in 1972. It was a puzzling decision, considering so many prominent figures in recent conservative politics hail from Wisconsin – including former Republican House Speaker and Vice Presidential candidate Paul Ryan, former GOP chairman Reince Priebus, and the highly polarizing former Republican Governor, Scott Walker. That and the fact that despite consistently voting for the Democratic candidate for President since 1984, the margin of victory consistently was narrow.

So, what happened in Wisconsin?

Enter The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker by Katherine J. Cramer, originally published in March of 2016, just eight months before Hillary Clinton’s fateful campaign came to what seemed to so many its impossible conclusion.

Beginning in May of 2007, Cramer, a professor of political science at the University of Wisconsin – Madison and a Wisconsin native, set out across her home state, inviting herself into conversations with ordinary people in over two dozen communities; she continued to join these conversations over the course of over the next five years, until November of 2012. The purpose of this expedition throughout many corners of the state was an examination of public opinion and political consciousness in an innovative way — not through traditional surveys and polls, but through actual face-to-face interactions with politically engaged Wisconsinites.

Through these conversations, Cramer uncovered a pervasive and deepening rural consciousness. To understand rural consciousness is to understand the lens through which rural people view politics and events that influence public affairs, and thus the lens through which rural people understood the changing world around them and critical events such as The Great Recession, the election of Democrat Barack Obama as President, and Walker as Governor of Wisconsin. Cramer’s book explains in detail how this emerging rural consciousness evolved into a full-blown politics of resentment and left the state ripe for the rise of Trump’s brand of right-wing populism.

My first encounter with Cramer’s work came a year ago, during the summer of 2019. I had recently graduated from the University of Texas at Austin with my Master of Global Policy Studies and was preparing to apply for a Master of Public Health. As I was creating an intellectual frame for how I wanted to pursue my studies of public health and its interaction with politics, policymaking, and voter decision, I developed a fascination with the Upper Midwest, and wanted to further explore the issues facing voters in these states.

I made my way through a few articles and studies on my search for a better understanding of voters, but when perusing books online, I came across Cramer’s work and the keywords in the title of the book stood out to me. Resentment. Rural. Scott Walker. I ordered the book for my e-reader, and I was immediately hooked.

Over the course of a few days, I flew through it, and could only think one thing, “This is the one. This is the book that Hillary Clinton should have read.” I’ve been lauding Cramer’s work to friends and colleagues ever since I first read it, and with the election coming up again, it seemed the appropriate time to read the book anew and conduct a proper review of this essential scholarship and remind us of the most salient issues driving voter decisions in what will be again a critical battleground state. And though the book is now over four years old, the issues it explores are as current and relevant as a column in this morning’s paper as fallout from a police shooting in Kenosha.

A zero-sum way of reacting to public affairs

Cramer’s findings, in short, were that throughout Wisconsin there was – and is — a growing sense among rural people that they are marginalized because they are rural, that those in positions of influence view them as “rednecks” or “hicks,” and are dismissive of their needs and concerns. As the economic disruption of globalization and events like The Great Recession impacted rural areas profoundly, this sense of rural consciousness sharpened itself into a politics of resentment, a zero-sum way of reacting to public affairs.

A politics of resentment develops when these contours of rural consciousness and the sense of being marginalized become part of what it means to have a rural identity. The identity moves beyond just an identity of place and expands to include an emotion of resentment and fear of economic insecurity.

To be rural means to be deliberately and systematically ignored by those in power. To be rural means ridicule and derision for one’s way of life and one’s values. To be rural means that you spend long hours, working physically demanding jobs for ever-diminishing returns. To be rural means that you pay more than your fair share into the system, and because power is held by urbanites and elites who do not understand and often look down upon rural life, you and your children will not receive the resources needed to sustain an increasingly difficult rural existence. To be rural means to be left out.

With such an intensified, adversarial, emotional, and divisive political environment, the atmosphere was just begging for a controversial figure, with controversial methods, to step in and seize the moment. Cramer correctly attributes this environment of resentment to the rise of Gov. Walker, but really Walker was just the tip of the spear.

A project to examine not what, but how Wisconsinites think

Cramer makes it clear that the purpose of her study is not to determine what Wisconsinites think about various political issues in their communities and state, and importantly, not to determine how correct ordinary Wisconsinites are in their interpretation. Rather, her work sought to better understand how people think about these issues and how they come to conclusions and make sense of the political world around them.

One common belief common among urbanites is that rural people are simply “voting against their best interests” because they have been hoodwinked or duped by politicians playing into their superficial social and cultural views, their racial or nationalist prejudices, and their lack of a comprehensive understanding of public policy. While this belief probably has significant truth to it, defaulting to this notion about rural people risks evolving belief into fallacy, which further distances urban and rural people from coming to an understanding. Thus Cramer set out, with Wisconsin as her window, to construct a more complete picture.

Many might find Cramer’s research methods unorthodox, and perhaps to some degree unscientific. They are, and that is OK. Conversations with 27 groups, some she visits once but many she visits multiple times over the course of five years, in randomly selected communities across Wisconsin, cannot deliver an indisputable conclusion that we can point to and say “This is what rural people think about Issue X” or “This is why rural people will vote for Person Y instead of Person Z”. The purpose of this work is not to make such determinations on a massive scale, but rather to use candid conversations to give participants a chance to voice their concerns, demonstrate their methods of reasoning, and draw attention to the issues that are driving the way in which they make sense of politics.

There is value in letting people explain their thoughts and reasons for their view of the world, something that has become increasingly difficult as this country became more polarized, as Cramer points out:

“We would do well to acknowledge that sometimes there is no substitute for sitting down with people and listening to their perspectives in order to measure what those perspectives are… My intention is to listen to and draw attention to these perceptions in order to better understand the political choices that they bring about… These understandings, whether or not one agrees with them, have roots and reasons behind them.”

Why do people believe in what they believe?

Political scientists that seek to understand voter decisions are on a constant quest to determine the basis for political beliefs. Why do people believe in the ideologies, value systems and partisan camps that they do? What entrenches these beliefs? What can encourage shifts in these beliefs? Are these beliefs inevitable or predictable based on class, race, economic status, or geographic location?

As human beings, we largely make sense of our world through categories, and we use these categories as a means to place ourselves within the social environment around us. Over the course of our lives we know which social groups we belong to, which social groups we do not belong to, and this distinction creates our social identity.

Cramer defines social identities as:

“Identities within social groups. These may be small or large – from friendship groups to society-wide categories like ‘women’ – but they serve as reference points by which people compare themselves to others. These identities help us figure out which people are on our side. They help us figure out how we ought to behave and what stances we should take. They even influence what we pay attention to. Because of all that, they affect what and who influences us.”

On how social identities influence political decisions, Cramer explains:

“Not all social categories are relevant to politics, but it does not take much for a social category to have an impact on the formation of preferences regarding the distribution of resources – an issue at the heart of politics… in the realm of public affairs, the distribution of resources is often portrayed as a zero-sum game. There is only so much money to go around. If I allocate it to my group, yours will not get it. Therefore, how people conceptualize the outlines of us and them likely influences what types of policies they are willing to support… People are especially likely to rely on their group identities in situations of uncertainty.”

Cramer quickly discovered that many of her conversations featured a hostile ‘Us vs. Them’ mentality, in other words, focused on the disconnect between ‘Wisconsin-residents-like-me’ against ‘Wisconsin-residents-unlike-me’. More specifically, the common feeling was that ‘Wisconsin-residents-unlike-me’ hold all the political power, resources and the instruments of their distribution, and access to prestigious education, while not possessing the same work ethic, values regarding the distribution of resources intimate knowledge of the way things should be in different parts of the state, and commonsense wisdom.

The contours of rural consciousness driving The Politics of Resentment

When Cramer originally began her project in 2007, it was not her intention to focus on the divide between rural and urban identities. But through the course of her conversations, and as events such as the rise of Gov. Walker transpired, it was clear that rural identity was a powerful driving force in the way people interpreted and reacted to these events.

Through her conversations, Cramer centers on three main contours that contribute to the lens that shapes rural consciousness:

“I argue that there are three major components of the rural consciousness perspective: a perception of that rural areas do not receive their fair share of decision-making power (who makes decisions and who decides what to even discuss), that they are distinct from urban (and suburban) areas in their culture and lifestyle (and that those differences are not respected), and that rural areas do not receive their fair share of public resources.”

First, rural consciousness views power and decision-making as something that is overwhelmingly happening away from rural areas and by people who do not understand the needs of rural people. In other words, power sharing in Wisconsin is “place-based injustice.” This means power is held in Madison and Milwaukee, is only concerned with the needs of people in those two metropolitan areas, and everyone living north of State Highway 21, known locally as the “Mason-Dixon Line,” or elsewise “Outstate” (meaning outside of the Madison/Milwaukee areas). Those outside of this zone of influence are not consulted, nor fairly represented, and consistently feel their concerns are dismissed as backward and people there are disregarded as “a bunch of rednecks” who do not know what is best for themselves.

Second, those in power, being urban or otherwise non-rural, do not share the same values as rural people, and therefore are incapable of understanding the needs and wishes of rural people. This is especially pronounced when examining how rural people understand the concept of hard work. One quote from Cramer’s book that stands out, in reference to university professors – “they shower before work, not afterwards.”

Bluntly, rural life is hard and getting harder. It is physically demanding. A great deal of it takes place outdoors in less than perfect conditions. But despite all that, there is a great deal of pride in the hard work that comes with a rural life. Deeply rooted in this conception of hard work is that those who do work hard are deserving of resources, and those who do not work hard are undeserving.

Third, available resources in the state are deliberately held back from rural people in order to favor those in urban areas. Not only that, but the resources that do exist are not intended to meet rural needs and wants, and thus Wisconsin (and the United States in general) is seen through rural eyes as being plagued with distributive injustice.

To illustrate how this works, higher education serves as a useful example. It is safe to say that everyone wants their children to attain the level of education they need in order to succeed. But the ways in which success in education are defined can vary greatly.

Cramer explains:

“It tended to be the case that higher-income folks talked about education as a means toward self-actualization, networking, and professionalization and as an important element of a healthy democracy. But lower-income folks talked about it as a means toward a job. They wondered aloud why anyone would spend all that money on a degree from UW-Madison when a two-year degree would get the person into a job more quickly or when attending another decent UW system school would get the person a much cheaper degree.”

First, from this point of view, a UW-Madison degree with all its prestige is not necessarily more valuable (a means toward gainful employment) to someone in a rural context but is certainly more expensive. Second, because of the price tag on an education from UW-Madison, it is more likely that urbanites who already have access to financial resources and the ostensibly better funded public schools will be able to send their kids there. Third, it was a common complaint in Cramer’s conversations that UW Madison did not really bother to recruit students from rural Wisconsin anyway, nor did they provide resources for rural students to cope with the radically different urban life on campus in Madison.

The might of UW-Madison stands in sharp contrast to rural people to their local schools, which have been shutting down as rural areas have lost population and the tax base to fund them. The local school is often a symbol of these towns, and when they shut their doors for the last time, it feels like a nail in the coffin for a dying community. It is not difficult to see how resentment might develop. UW-Madison on one hand, with its legions of public employees with healthcare plans and pension funds, operating to serve the interests of urbanites and elites, and its perceived reluctance to recruit rural students, and on the other hand, decrepit and dilapidated local schools left to struggle and shutter, leaving local children with bleak prospects.

The way in which UW-Madison is viewed in rural Wisconsin is similar to how many public institutions would be seen through rural consciousness – with heightening animosity toward the resources it receives and especially toward the people that it employs, who are seen as receiving benefits at taxpayer expense (such as healthcare) that are increasingly scarce for rural people.

Throughout Wisconsin’s history, politicians have tapped into rural consciousness in order to win votes and rally support on both sides of the political spectrum – including Wisconsin’s early 20th Century Gov. Robert La Follete, considered by some the Father of Progressivism in the United States and third-party candidate for President in 1924, as well as Republican Congressman Joseph McCarthy, the hyper-conservative ring-leader of the post-WWII paranoid frenzy to seek out alleged communists in positions of power and the entertainment business. And thus, rural consciousness aligning itself with conservatism is not necessarily inevitable.

The complexity of race as a factor in the anger against distributive injustice

Race is certainly another component of rural consciousness, and there are definite racial undertones to terms such as ‘urban’, ‘inner city’, and references to people that depend on government services as ‘undeserving’, and we are certainly seeing this play out as events in Kenosha continue to polarize the state. Cramer argues that while this is important, it does not explain enough. Wisconsin is an overwhelmingly white state, with whites comprising about 87 percent of the population. People of color in Wisconsin tend to live in either heavily segregated Milwaukee or Madison, and those in more rural parts of the might have little to no direct interaction, though that is changing. While comments about distributive injustice at times were directed at people concentrated in urban areas, she also encountered similar comments about white neighbors. Race cannot be removed from the equation, but also must not be the only variable.

The few openly racist comments she encountered were directed toward Native Americans (with stereotypes of being funded by the government or casinos and drunken), and though she does not reveal which communities she conducted these conversations, it is likely these rare comments came from people living in close proximity to one of Wisconsin’s 11 federally-recognized tribes.

It is probable that openly racist beliefs about other minority groups, even among those who hold them, are recognized as taboo, and therefore likely omitted from recorded conversations with a political science professor from UW-Madison. Race is important, but Cramer wants us to make sure that we do not focus on that at the expense of attention to other contours of rural consciousness.

Cramer explains –

“If we conclude that rural consciousness is just racism dressed up in social science jargon, it allows us to overlook the role of antigovernment attitudes and preferences for small government here, Tea Party messaging appeals to racism, but it also resonates with many of the perceptions of inequality and alienation that from government observed in the conversations presented in this book.”

“But racism today is not simple. Race is not something that we can siphon off from place and class in the contemporary United States. Patterns of discrimination over centuries means that race colors our impressions of what kind of people are where and our willingness to share resources with them.”

Making sense of the ruckus – Scott Walker and Act 10

Before we continue, it is worth taking a moment to contextualize Cramer’s findings in the political events that transpired in Wisconsin as she conducted her research, which means we must understand Scott Walker and his rise to power.

After a failed bid for the Republican nomination for Wisconsin Governor in 2006, Walker ran again in 2010, and was the early favorite for the nomination. Walker ran on a very conservative platform including an opposition to abortion in almost any case, opposition to same-sex marriage, and support for strict stances on immigration. But most noteworthy of all, Walker promised to cut wages and benefits for public employees as part of his plan to balance the state budget without raising taxes.

Walker wasted little time, introducing his Act 10 legislation, also referred to as the “Wisconsin Budget Repair Bill,” on Feb. 14th, 2011, just over a month after taking office. This legislation would implement many changes for public employees, including increased contributions from public employees toward their pension funds and health insurance and strict limits on the ability of public employees (most notably, teachers) to collectively bargain for wages. The latter severely impaired unions’ ability to operate on behalf of public employees, 36.2 percent of which held union membership.

Walker’s election, and the series of vicious battles leading to the passing of the legislation, shocked many of the urban and educated people of Madison. Protests erupting in opposition to Walker and the legislation are estimated to have drawn over 100,000 protesters over the course of five months. The protests gained national attention and drew visits from figures on both sides of the political spectrum, including partisan political media firebrands Michael Moore on the left and Andrew Breitbart, as well as the former candidate for Vice President Sarah Palin, on the right.

The protests evolved into a movement to recall Walker, making him the third governor in the history of United States to face removal, as over one million signatures were gathered to force the recall election. In yet another shock to many living in Madison, Walker survived, beating Democratic challenger Tom Barrett by over 170,000 votes. He would win a second term in 2014. The same question faced Democrats in Wisconsin that would face much of the country two years later, “what happened?”

Walker used the swelling support for Tea Party politics, the economic tremors of the Great Recession, and traditional conservative positions to win the election for governor. But it is curious that he was able to do so in 2010, sandwiched between 2008 and 2012, elections in which Barack Obama carried the state.

What really made Walker successful was tapping into rural consciousness and running on the promise that he would take on public employees and their benefits directly. Frankly, he said he was going to stick it to the liberal, urban, publicly employed elites of Wisconsin, take them down a peg from their self-righteousness and pomposity. And that is exactly what he did.

Cramer observed that the perception of Walker’s election and the passing of Act 10 in rural Wisconsin was not necessarily perceived as victory for small-government or a particular policy preference, but more a victory for “small-town Wisconsinites like themselves.”

When the protests in Madison in opposition to the legislation erupted, Cramer says, “Many of these folks had a visceral, negative reaction to the protests. To them, this was not a display of Wisconsinite ingenuity and collectiveness but of urban excess and arrogance.”

In such a political environment, the perception of public affairs is often reduced to something that looks like this diagram:

rural folks like me = hard-working people = nonpublic employees = deserving

versus

urbanites = people who don’t work hard = public employees = undeserving

With this understanding of political choice, public affairs become a zero-sum, tooth-and-nail fight between ‘Us’ and ‘Them’. If the urbanites get something, rural folks like me have lost something.

A controversial person with controversial methods

Donald Trump seized upon, intentionally or otherwise, the same character of Walker’s promise to punish ‘them’ and expanded it to enormous proportions. Trump’s campaign for President promised rural people much of the impossible. Manufacturing jobs long lost to the forces of globalization would return, demographic changes would be halted by closing the avenues of immigration, the elites who are responsible for rural exclusion and marginalization would be punished, and through his election, he would make rural America what it once was, at least as it is understood through the lens of rural consciousness.

As it turns out, Donald Trump carried Wisconsin by a narrow margin in 2016. Hillary Clinton, and her campaign, utterly failed to recognize the danger presented by the rise of Walker, and the growing politics of resentment. Unfortunately, Hillary Clinton represented the establishment and elite character more than perhaps any other American, and thus her campaign was effectively burned in effigy by those susceptible to the politics of resentment. Without a coordinated strategy to counter these perceptions, and without paying so much as a single visit, the Clinton campaign lost states that Democrats had reliably carried for decades.

Conclusion: to understand — and understand what can be done?

I understand that many reading this are likely outraged by a lot of what has been presented above, and Cramer sympathizes in her writing. It should be stated again that the purpose of her work is not to determine what people think, and especially not to evaluate how correct rural Wisconsinites are in their assessments.

Nonetheless, Cramer dedicated a chapter of the book to understanding how accurate the beliefs held by rural people – whether or that they’re actually left out or pay more than their fair share through taxes while receiving a disproportionately low return of resources. The results of her investigation are mixed. Rural people in Wisconsin at the time of her study, might actually receive more tax dollars per person than urban people, but these determinations were, and remain, difficult to make conclusively.

Rather, the point of this study is to understand how rural people come to the conclusions they do about politics, and why they might make the voting decisions that they do. In the end, what matters is that the perception of rural marginalization is strong, and the response to it by rural people is equally strong — as evidenced by the rise of Walker and Trump.

So, what can be done? Cramer offers some important suggestions for a course forward:

- “Perhaps state, federal and even county legislation is too often applied to all types of places equally. Maybe more programs should be tailored specifically for rural needs and crafted with recognition that not all rural areas are the same… We need geographic cooperation as well as bi-partisanship. Within state legislatures, something as simple as an exchange program, in which representatives from urban districts spend time in rural districts and vice-versa, could help improve empathy for the needs of people outside one’s own type of district.

- One of Cramer’s interviewees, labeled ‘Sue’, in a rural tourist town, echoes this sentiment:

- “Exactly, (responding to a comment about the need for improved services offered throughout the state) but it should be a shared thing. I mean why can’t we look at that? Or at least put a state office up here, with all the communication.” [Agreement all around: “That would help.” / “That’s a thought / “Great idea.” / “Absolutely.”]”

- The state government needs to improve visibility about the programs that it is offering rural people, “The second thing rural resentment toward the cities suggests about public policy is that some of the resources rural communities are receiving are invisible to the people who live there.”

- “If the people I spent time with had perceived that policy makers had listened to the concerns of rural residents before creating government programs, would they have felt differently about these programs?”

- “At my root, my hope in writing this book is that more and more people redirect the energy they use to engage with public issues away from criticizing their fellow citizens and toward improving the policy process to ensure that it is responsive to the needs of all people. That is asking a lot. In an atmosphere of resentment, it is tough to take the high road and operate on a belief that all people are, at root, good and deserving of respect. Our current politics give little incentive for elected officials to pursue such behavior. It is time for those of us with the power to vote to demand it of them”

I have few minor critiques of the work, or rather ways it could be expanded.

For one, the book spends zero time investigating religion, which is almost certainly a major point of contention between rural people and their values, and their perceptions of urbanites. Second, while it is difficult to do for reasons explained above, a clearer picture of race in rural consciousness needs to be explored. True, this is difficult to accomplish through conversations in which people may feel compelled to avoid the taboo of racist beliefs, but the absence of openly racist comments within Cramer’s conversations is suspicious. Third, Cramer spends a bit of time exploring how the ideas of rural consciousness are transmitted, exploring local news media for one, but does not mention social media. Certainly, in the five years that Cramer conducted her conversations, social media was in its nascent stages and well shy of the titanic force it is today. There must also be more attention paid to the development of right-wing media over time – from the talk radio programs of Rush Limbaugh, to the rise of Fox News, and finally Internet-based personalities like Alex Jones.

To conclude, I do not intend this book review to serve as a component of a campaign strategy for Joe Biden, or Democrats in general, though despite early polling, the election is likely to be close. Instead, for me, the brilliance of this work of scholarship is firmly rooted in its methodology, and that is where policymakers and political scientists alike can derive the central lesson. There is value in taking a step back from massive demographic analyses, opinion polls, and the search for a generalized truth about what people think and believe about politics, and just listening to what individual people are saying. I believe that Cramer has but scratched the surface, below which a whole new realm of public affairs understanding can be reached.

We do not know at this time how the election of 2020 will turn out. Certainly, it will be close, and to the horror of urban liberals everywhere, enthusiasm for Trump remains fervent. Safe to say that polarization in the United States is not going anywhere, regardless of the election’s outcome. The rural / urban divide is certain to expand, but we must not surrender our capacity to listen to and respect one another, or the chasm created by resentment will surely swallow us all.

Buy this book with a click to your local bookseller:If you like what you’ve been reading, please click here to subscribe and we will send you updates and our newsletter.