Leadership in the time of COVID-19 – A CEO’s journey

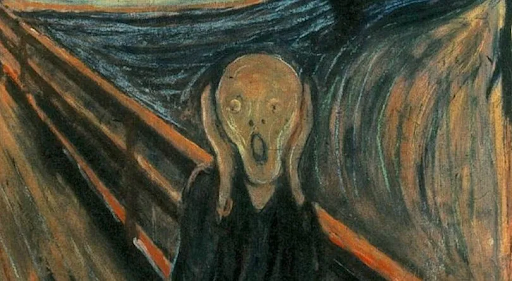

Fear, euphoria, depression, acceptance, and imagining what lies beyond

Part I of V: Fear

It was late in the afternoon of March 6. A month or so of headlines had focused on this strange new virus emerging in China’s Wuhan province, killing the then-staggering number of 3,000 — almost all of the victims in that country. The movie “Contagion” was already trending in the top 10 most watched movies on iTunes for the past month. Domestic attention was riveted on Washington state, where seven residents of a nursing home had died in the “epicenter” of a malady which at that point had killed 14 in the United States. Tensions were rising, of course, as the World Health Organization declared a global total of 100,000 cases, travel restrictions were being debated, and the CDC was discouraging domestic air travel. Two days before, Texas’ first case of COVID-19 had just been confirmed in Fort Bend County.

I was concerned. I wondered if this might compare with the “swine flu” outbreak in 2009 that ultimately killed more than 3,000 people in the United States before receding. I felt unease, but hardly anticipated what was to soon ensue.

And then the emails began, the texts lit up my phone. Austin Mayor Steve Adler had just cancelled the SXSW festival, the lodestone of Austin’s tech and music economies. I knew this was likely. My good friend Josh Baer, CEO of Capital Factory, had been discussing it with him, and I knew they were struggling with it. SXSW was important to many, and that included my company, data.world – we always showed up in force and welcomed our many customers and partners to town.

“This is real, and this is real bad,” I said out loud, to no one in particular. If the city was walking on a $380 million turnover on expected economic activity. If the mayor was taking this drastic a step just two days after his own chief health officer Mark Escott had given the festival the all clear… well, what was in store for my almost five-year-old start-up scarcely at the beginning of our most ambitious year for investment fundraising, new customers, revenue and growth? My anxiety, my unease, was instantly transformed to something far more profound. Fear descended upon me, as if from all four walls. Raw and unforgiving.

The jobless, the frail, the frontline, and injustice unmasked

In retrospect 10 months later, I feel a bit selfish in my immediate reaction. After all, I took my fifth company, Bazaarvoice, public when I was 40 and could have just retired. I was and am healthy and so are my wife and two children. Personally, we have the means to cloister and as a digital company, data.world is at the leading edge of those most able to shift to distributed work-from-home. My empathy was, and certainly now remains, with those on the front lines, those whose jobs disappeared, those suffering from the racial and economic injustice that the pandemic has unmasked, my friends who lost businesses they had spent their lives building, and of course those whose frailty made them most vulnerable to a plague that has since then taken some 360,000 citizens from our midst in the United States as I write this.

But these thoughts were not top of mind on March 6 and they only began to rise in the days to come. For I had more than 50 employees to worry about, and a score of investors. We were in the middle of the first quarter in our fiscal year with lofty goals that were set after beating our previous year’s goals and looking at a round of aggressive venture capital fundraising just beyond that.

“Team,” I wrote in one of my first all-hands pandemic memos a few days later. “We just had an executive team meeting and decided that starting on Monday we are shifting to a remote work from home policy for at least the next two weeks. The safety of all of you as our team – our company family – is of the most importance during this time.”

Looking back now, the idea that we might only be shuttering for a few weeks was not just naive, it was unrealistic. But only in hindsight. I made arrangements for the entire company to mobilize from home. I encouraged our employees to avoid Spring Break travel if possible, provision with enough food and prescription medicine, and embrace this then-new concept of “social distancing.”

As the news grew more dire each day

“I really think this time will bring out the best in us if we let it,” I wrote in another Slack post email as I tried to put a brave face on it all. “Let’s see how well we adapt to remote work – I’ve never run this type of exercise in my career and I’m looking forward to learning from the best of us in doing so. I believe our company has been built for the modern age from the beginning and older line companies will have a more difficult time adapting.”

I said that. I believed that. But did doubts linger? Of course they did.

Each day the news was growing more dire. On March 24, Mayor Adler issued the first stay at home order in Texas, one of the first in the nation. It was about the same day that I was participating in TED. For years I’ve joined these gatherings, which are held each spring in Vancouver, Canada. They’ve really pushed my thinking about our past, current, and future, and the people that attend are just incredible. This was the first held virtually, and it was a serious experiment for TED.

I was particularly eager to hear what Ray Dalio, the philanthropist and head of the world’s largest hedge fund Bridgewater Associates had to say. I’ve long admired his sage advice, global insight, and ability to see around the sharp corners of business. His counsel was spot-on at the time, but it hardly helped my mood.

“There are always stress tests that come along and COVID-19 is one of those,” I jotted in my notes of Dalio’s talk. He was encouraging about the global strength of the dollar as a kind of sea anchor in the storm but worried frankly about those outside what he called the ‘ring of support.’

But his warning that we could be looking at something of Great Depression scope was alarming, to say the least. He noted that at that date global markets were down as much as 40 to 50 percent depending on what currency you were trading in. His insight that the global markets had already shed some $20 trillion in value was chilling. Indebted businesses would fail. Supply chains would be wholly reshaped. Even hospitals, just as we most need them, could go broke Dalio warned.

“This is not just a recession,” Dalio said. “It is a breakdown of how we deal with money and credit.”

I took a long walk on the challenging hills near our home. I tried to push away the fright, telling myself that if this pandemic was creating fear for me, for so many it could be nothing less than abject terror. I really understood that the world would never be the same.

“Choose positivity,” I wrote shortly afterward to my colleagues. “There are a lot of positive news stories out there, like (British manufacturer) Dyson producing ventilators. The news is full of fear of death and infections and not enough hospital beds. Those are very real things, but you’ve got to also tune in to the positive and fill your soul with that, too.”

I tried to take that advice myself.