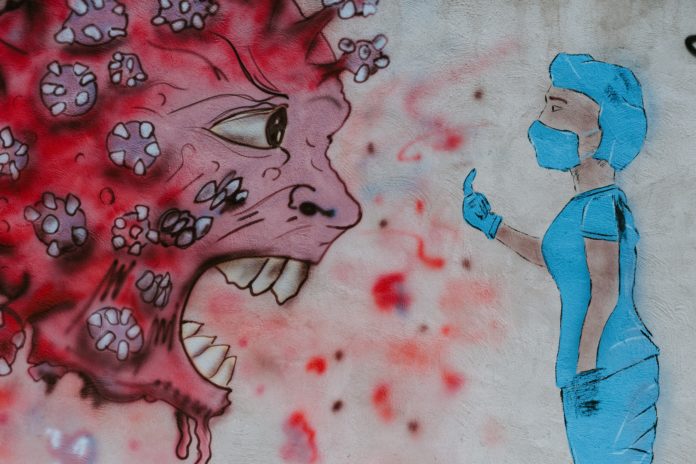

Photo: Ashkan Forousani via Unsplash

The Affordable Care Act, or ACA, the signature policy of President Barack Obama’s administration, was the culmination of nearly a century of contentious policy battles over health reform in the United States.

The future of the sweeping ACA – with implications for the health care of millions in Texas and the nation — remains acutely uncertain. The ACA will face a direct challenge in the Supreme Court on Nov. 10, in a case brought forth by the state of Texas. During the opening round of confirmation hearings for would-be Justice Amy Coney Barrett, the issue was deservedly put front and center, despite the efforts of John Cornyn and other Senate Republicans to obfuscate and trivialize the matter.

Barrett clearly stated she believes the ACA is not protected from the pending challenge from Texas by any legal precedent:

“There is not precedent on issue that’s coming up before the court. It turns on a document called severability, which was not an issue in either of the two big Affordable Care Act cases.”

In many ways the upcoming election between Republican Donald Trump and Democrat Joe Biden also represents a partial referendum on the law as well. Trump continues to promise to eliminate the ACA but somehow preserve the popular aspects of the law, even tossing out an executive order that allegedly protects pre-existing conditions. Biden, meanwhile, has promised to expand upon and improve the ACA. Despite the precarious future of the ACA, we should look carefully at how it succeeded in Texas and what gaps remain in the state with the highest percentage of uninsured residents.

While the landmark act, known as colloquially as Obamacare, reduced the ranks of the uninsured by more than 20 million Americans nationwide as of 2019, and saved an estimated 19,000 American lives, it left a far smaller mark in Texas. Among the dozen states that opted of the plan’s Medicaid expansion provision, Texas failed to take advantage of the ACA’s most effective tool to extend care to the poorest Texans.

By rejecting Medicaid expansion under the ACA, Texas turned away an estimated $100 billion in federal health care assistance, in a state where hospitals average an uncompensated $5.5 billion in spending on the treatment of uninsured Texans. Despite the obvious benefits and popular support, political opposition to the ACA in general and the Medicaid expansion stipulation in particular by elected state officials in Texas is well-documented and continuous. This opposition has continued even in the face of a terrible pandemic that has taken the lives of nearly 17,000 Texans.

The catastrophic repercussions of Texas’ failure to adequately expand health coverage to the poor was explained to NPR by Stacey Pogue, an analyst at Every Texan, an Austin-based non-profit that advocates for social justice:

“We need to do everything we can to make sure people are not afraid to get tested because of cost, or are not afraid to get treatment because of cost … And states like Texas with such a huge uninsured population, that’s a huge barrier to our public health response.”

Gov. Greg Abbott, like President Trump, continues to promise that the state of Texas is ready with a plan of its own, that will protect pre-existing conditions and expand affordable health insurance throughout the state.

In 2018, as the legal fight against the ACA from the state of Texas began, Abbott defended the challenge:

“As the ACA lawsuit goes through the appellate process, Texas will work with the administration to get appropriate waivers from federal law allowing insurers to provide coverage at lower rates while ensuring that Texans with pre-existing conditions continue to have access to quality health care… Additionally, Texas will begin the process of reforming state regulations and proposing changes to laws that will achieve those same goals. Importantly, Texas will strive to expand health care insurance coverage, reduce the cost of health care and ensure that Texans with pre-existing conditions are protected.”

Pogue, this time speaking to the Texas Tribune, countered:

“There’s been absolutely no plan whatsoever put forward by state leaders to try to replace any meaningful part of the Affordable Care Act that ensures either affordable coverage or preexisting condition protections.”

Whether or not the ACA survives the Supreme Court challenge remains to be seen. Should the ACA endure, it is likely that Texas will continue to reject the billions of dollars in desperately needed benefits offered under the law. Should the ACA be eliminated, it is safe to assume the state government will not actively pursue a prudent strategy to expand health coverage to the millions of uninsured people throughout the state.

Texas cities and counties could fill the policy vacuum left by the state

But what if the cities and counties in Texas with the most need, and the necessary political will, had the authority to do what the Texas Legislature and governor snubbed their noses at?

An intriguing solution that could be perfect for Texas has in fact been posited by Jeanne Lambrew, now the Commissioner of the Maine Department of Health and Human Services, and Jen Mishory, senior fellow at The Century Foundation, a policy think tank. It was within an analysis of Medicaid in 2018 that they identified a roadmap that Texas might well want to follow.

What if cities and other localities such as counties, Lambrew and Mishory asked, were allowed to bypass hostile state governors and legislatures, and implement Medicaid expansion solely within their borders?

Among their most prominent examples, they pointed directly to Dallas and Harris Counties as being two of the most populous counties in the United States that lie within the borders of states that had not yet opted into Medicaid expansion. We can certainly expand their argument to include Travis County, the state’s fifth largest, as well.

A brief history of the ACA’s underuse in Texas

Before we can explore the viability of this suggestion, let’s first review the history of the ACA in Texas, so that we can understand how we got to where we are, and how we might be able to move forward.

In 2018, 18 percent of all Texans did not have health insurance, more than any other state. The uninsured rate in Texas is double that of the national average of 9 percent, and the uninsured rate of Texas is 4 percent higher than the rate in the nation’s second least insured state, Oklahoma. 11 percent of children in Texas are uninsured, more than double the national rate of 5 percent. To highlight this point, 20 percent of all uninsured American children live in Texas.

In the Austin-Round Rock metro area about 11.9 percent of residents remained without insurance in 2018. This uninsured rate was lower than that of Texas overall, less than Houston’s rate of 18.2 percent, and much less than the nation’s worst Dallas rate of 24.4 percent.

Still, Austin-Round Rock’s rate was high compared with other cities across the United States such as Denver (6.5 percent uninsured), Seattle (4.15 percent uninsured), or Nashville (6.1 percent uninsured), just to give a few examples.

As alarming as these statistics are, before the ACA, these numbers were even worse. In 2010, the year that the ACA was signed into law, 23.7 percent of all Texans were without health insurance – a total of about 6 million residents spread throughout the state. Since the insurance marketplace offered by the ACA became available, about 1 million, or 5 percent of the state’s total population, gained health insurance.

Austin-Round Rock’s rate improved since the passing of the ACA as well, falling from an uninsured rate of 14.4 percent in 2015, to the 11.9 percent rate in 2018. This came about through a combination of local funding and promotion of ACA programs and the use of the Medical Assistance Program (MAP), which is not an insurance plan, but does provide health coverage assistance for residents at or below 100 percent of the federal poverty line.

Central to the ACA legislation, and perhaps the most important aspect of the ACA in terms of guaranteeing health care access for all Americans, was the pursuit of Medicaid expansion to all 50 states. The expectation was that more low-income individuals – unsurprisingly those Americans who suffer the greatest disparities in access to quality health care and suffer the worst health outcomes — would be provided coverage through expanding Medicaid at the state level.

Under the plan, every state would be mandated to expand Medicaid coverage for those with incomes at or below 138 percent of the federal poverty level. At the time of the legislation this was $27,000 for a family of three. The plan provided that the federal government would offset the full cost of expanding Medicaid to a state’s residents, with that reimbursement dropping to 90 percent of the state’s Medicaid costs by 2020. It was estimated that Medicaid expansion to the states would have expanded coverage to 17 million non-elderly adult Americans.

In 2012, the Supreme Court ruled that the portion of the ACA that mandates states expand Medicaid in exchange for federal reimbursements was unconstitutionally coercive of the states, and though the policy itself could remain intact, the states must choose for themselves if they want to participate. As of 2020, all but 12 states have enrolled in the Medicaid expansion plan.

In response to the Supreme Court ruling, then-Gov. Rick Perry of Texas opposed Medicaid expansion into Texas, and in doing so, turned down what could have been as much as $7.7 billion in federal funds to expand health insurance to the state’s residents.

Perry wrote in a letter at the time:

Waiving the Medicaid expansion… “should give Texas the flexibility to transform our program into one that encourages personal responsibility, reduces dependence on the government, reins in program cost growth and efficiently improves coordination of care.”

Perry’s rhetorical sophistry was likely motivated by a couple misconceptions: One, that repealing and replacing the ACA would be a popular and viable pursuit for Republicans going forward; and two, that he himself would be a contender for the 2016 GOP nomination for President.

Perry could not have been more wrong on every point. And the consequences for Texas are terrible, especially amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

With insurance tied to jobs, the number of uninsured Texans is skyrocketing

Certainly, what former Gov. Perry meant by “personal responsibility” was to suggest that if someone is responsible enough to have steady employment, then they have managed to cover their health concerns all on their own.

Without the Medicaid expansion stipulation implementated in Texas, nearly half of all Texas residents are dependent on Employer Sponsored Insurance, or ESI, for their health care. Many ESI plans tend to feature high-deductible and increasing premiums, and the ability of ESI plans to a cover significant portion of the population is vulnerable to economic downturn.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began to take hold of the state around March of this year, 1.6 million Texans have lost their health insurance along with their jobs, and a new report from the Episcopal Health Foundation found that a staggering 27 percent of the estimated Americans falling into a health coverage gap — those who made too much money to qualify for Medicaid and too little to qualify for an ACA subsidized plan – will be found in Texas in 2021. Nationwide, 36 million Americans have filed for unemployment since the pandemic began, 2 million of those in Texas, many of them filing for unemployment for the first time.

As a result, the failure of Texas officials to expand Medicaid into the state has resulted in an increase in dependence on government, a rise in the cost of health insurance programs and treating uninsured Texans, reduced the efficiency of the care provided, and weakened the ability of individual Texans to be personally responsible for their mounting health care needs.

How local government could expand Medicaid on their own

If the state government continues to refuse Medicaid expansion, and without substantial political change at the state level, we must seek other solutions. This brings us back to the idea put forth by Lambrew and Mishory – what if we allowed cities and/or counties to expand Medicaid under the same terms offered to states by the ACA?

The proposition involves overcoming some difficult administrative logistics and would need some legislative ingenuity in order to be implemented. But it would be eminently doable.

Towns, cities, or counties would need to be able to secure their share of their state’s costs of Medicaid expansion, and work with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, or CMS, to create eligibility systems for residents within their jurisdictions. Enrollees within cities would then receive benefits similar to the benefits they would receive if their state had opted to expand Medicaid.

This suggestion could go a long way to filling in the uninsured gaps left by the refusal of Texas officials to expand Medicaid, considering the high rates of uninsured people living in the largest cities in the state.

Roughly estimating, we can assume that 24.4 percent of all Dallas residents (approximately 328,180 in total), 18.2 percent of all Houston residents (approximately 423,330 in total), and 11.2 percent of all Austin-Round Rock residents (approximately 247,180 in total) are currently uninsured.

If these residents gained health coverage through Medicaid expansion within these jurisdictions, that would reduce the total number of uninsured Texans by nearly 1 million in those three cities alone, or by nearly a fifth. If the initiative proves successful it could serve as a galvanizing message that Medicaid expansion is worth implementing in the rest of the state.

This initiative is much easier said than done, and it likely cannot be done without the approval of the state government. The state would have to agree to a so-called Section 1115 waiver, which allows a state the ability to experiment with novel approaches with Medicaid than what is required by federal statute. A few states have used Section 1115 waivers in innovative ways to reform their health delivery systems and meet their states unique needs, most notably Michigan’s use, which targets the specific health needs of Flint, the city now all but synonymous with lead pollution in its water.

It is unclear if such a waiver could be granted that would enable individual cities or counties to negotiate for Medicaid benefits, or if the state of Texas would be amenable to exploring this possibility. Still, the chance to bypass the difficult politics of participating in a portion of the ACA may be attractive to the Republican-controlled state government, which is unable or unwilling to address the issue of uninsured Texans, hindering efforts by city leadership to protect their residents.

The obvious drawback to this plan, though, is that it could prove hugely beneficial for residents of major cities, but would further marginalize uninsured Texans living outside a participating metro area. A great deal of the political push for Medicaid expansion comes from Texas cities, and without that push, rural uninsured Texans might lose an important set of advocates.

Nonetheless, amid the COVID-19 pandemic that affects Texas cities in a unique way, we must be willing to explore unique possibilities to expand health care to as many Texans as possible. Texas cities suffered greatly as a result of the pandemic, and more residents of these cities risk losing their health insurance every day. As long as the ACA remains law, it is essential to build on what it has already done for Texas, and we must remember the spirit of its passage nearly a decade ago.

The time to act is now.

As President Obama put it on the seventh anniversary of signing the ACA into law in 2017:

“When I took office, millions of Americans were locked out of our health care system. So, just as leaders in both parties had tried to do since the days of Teddy Roosevelt, we took up the cause of health reform. It was a long battle, carried out in Congressional hearings and in the public square for more than a year. But ultimately, after a century of talk, decades of trying, and a year of bipartisan debate, our generation was the one that succeeded. We finally declared that in America, health care is not a privilege for a few, but a right for everybody.”