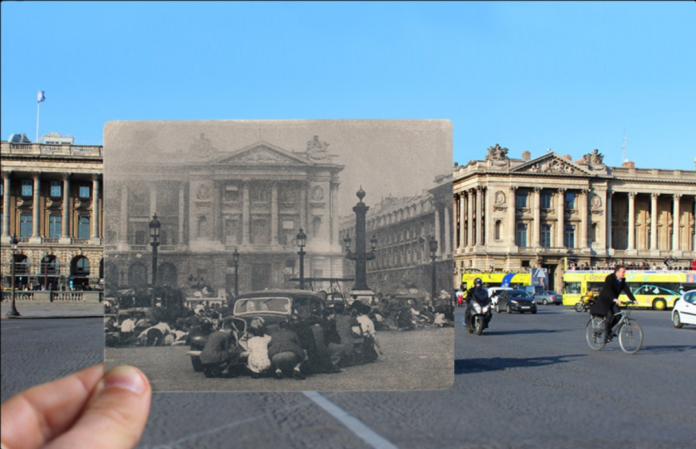

When the philosopher Walter Benjamin visited Paris on the eve of the Second World War he recognized that the City of Light, filled with the greatest artists and writers of its time, represented the apex of creativity. He also warned that it offered the “last sight” of a world hurtling toward destruction.

The Nazi invasion in 1940 placed the city in rapid and harsh lockdown. Overnight, the cafes closed, the bookstores shuttered, and the artists retreated to hiding. If they were lucky.

Benjamin was not so lucky. He joined millions of others who died at the hands of the Nazis, and their collaborators.

Paris recovered from the destruction to rebuild and thrive soon after the war. The road to recovery involved suffering, sacrifice, and the creation of a new city. The flamboyant pre-war community chronicled by Benjamin became the center for technical proficiency and industrial leadership in postwar Europe. The tourists only returned after the city thrived again.

Despite the mass death and destruction, Paris recovered because it drew on its inherited mystique and talent to reinvent itself. The capital of an empire became the hub of commerce on the continent, with the opening of countless headquarters for international organizations, Europe-wide institutions, and corporate enterprises. Charles de Gaulle, the leader of the anti-Nazi resistance and then president of postwar France, could not recognize his own capital. It had too many foreigners and businessmen, in de Gaulle’s estimation.

Contemporary cities, especially Austin, have a similar opportunity to draw on their strengths and past achievements to reinvent our world today. Contemporary cities also confront the same resistance from figures, like de Gaulle, deeply attached to the “last sight” of past glory. The challenge is to look forward, to emphasize change after destruction. The cities which have done this – Chicago after the great fire of 1871, San Francisco after the earthquake of 1906, Paris and London after the Second World War, and New York after 9/11 – have prospered. The cities that remained stuck in their moments of destruction – Galveston after the hurricane of 1900, Dresden after the Second World War, and Newark and Detroit after the riots of 1967 – have never recovered.

What does it mean to look forward after a period of devastation? What can we learn from history?

Money matters: Paris benefited after the Second World War from a massive infusion of money from the U.S. Army, and then the American-sponsored Marshall Plan. The dollars helped put citizens back to work, and they financed the building of roads, schools, and factories. American money attracted talent from labor unions, universities, and businesses across the continent. The dollars empowered those figures to become influential actors on the ground. Public financing is always crucial for key infrastructural investments, and local talent must step up to manage those resources effectively.

Cities today must do more than just meet immediate needs in the wake of the pandemic. The cities that will prove resilient, like Paris, will be the ones that make long term investments in human, social, and physical capital. City leaders must think big about communication, transportation, education, and other needs that will enhance opportunities for citizens across neighborhoods, classes, and races. Cities must not pursue funding primarily to cover sunk costs on projects and plans that might no longer offer the same promised value as before. With key funders – federal and philanthropic – cities must advocate for greater flexibility within lawful expenditure guidelines so they can look forward, rather than simply react. That was the genius of the Marshall Plan which, more than any program, provided forward-looking and creative Parisians with resources to build the new institutions their city needed. Dresden, at the same time, followed Communist Party requirements to build a one-party city and an extractive economy, not a forward-looking, dynamic community.

Mobilize the People: Postwar Paris was not designed or built by de Gaulle or any group of politicians. The city grew from the energies of the people who, after years of sheltering from Nazi crimes, came out to revitalize their society. Many of the most important actors were not elites, but shopkeepers, students, women, and other citizens who sought new opportunities for their families. They studied new subjects, opened new businesses, and even learned new languages. The innovations that rebuild a city after devastation are decentralized and diffuse. Scholars of Paris have chronicled the exciting atmosphere of experimentation – social and economic – after 1945.

Destruction of the old order should indeed open space for a nascent, uncertain, and experimental testing of boundaries. And ordinary people of talent and energy must play a central role, often replacing established elites. Cities must cultivate this dynamic today. They must bring new innovators into the conversation. They must empower them to try new things. Cities like Austin must build on their pre-pandemic openness to innovation and a robust entrepreneurial ecosystem. They must bring new innovators and creators into the conversation. They must empower them to try new things. The years after devastation are a time for youthful creativity in the most dynamic places. That was the story of Chicago after the fire and Paris after the war. It will be the story of cities that thrive after COVID-19.

Improve the Quality of Life: Residents who lived through the Second World War in Paris suffered deprivation, anxiety, and shock. And their lives remained difficult long after the armistice. The personal trauma lingered.

American and French authorities immediately made efforts to show that they intended to improve the quality of life for long-suffering citizens. They offered the most powerful ingredient for renewal: hope. In Paris, this meant efforts to improve health care and food access for all residents. It also meant widespread jobs programs, promising a wage to those who had been out of work for so long months and years. The early postwar welfare state made a promise of better living for those who were courageously re-making their society.

The arts were central to the postwar welfare state. So were efforts to cultivate healthier living environments, including cleaner streets and more accessible public parks. The New Deal was the key inspiration on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. The Civilian Conservation Corps, or CCC, created by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1933, employed three million young Americans (under age 30) to plant trees, clear land, and prepare numerous public spaces. American and French authorities used available resources to form local versions of the CCC, making Paris a more livable, healthy city after the war – less crowded and more green than it had been before.

Leading contemporary cities like Austin did not always offer their citizens the highest quality of life before the COVID-19 crisis. The new health and economic challenges will only deepen these concerns, especially for the most vulnerable urban residents. Instead of re-fighting old battles over land development and public safety, city leaders have an opportunity to invest in new efforts to enhance the collective quality of life. A return to renewal of programs like the CCC – employing citizens who have lost their jobs to improve their environment as they learn new skills – could give people renewed hope, belonging, and happiness in their home communities. Offering people a chance to contribute to the arts and environment in an enduring way can indeed transcend past differences, replacing some of the old ugliness with participatory beauty.

In cities like Austin where creativity thrived before the pandemic, the arts community can help author a compelling narrative of hope. Writers, painters, and musicians can help citizens process their COVID experiences, bringing diverse men, women, and children together in celebration of their common humanity. The arts allow multiple voices to express themselves and learn from one another. Offering people a chance to contribute to the arts and environment in an enduring way can indeed transcend past differences, replacing some of the old ugliness with participatory beauty.

Do it Now: We will never return to the “last sight” of Austin and other cities before the COVID-19 crisis. That is not a bad thing. As Walter Benjamin recognized more than eighty years ago, creative cities are always in flux, and they are at their best when they adapt, experiment, and use past greatness to inspire forward-thinking innovation, even radicalism.

This adaptive dynamic moves faster than ever today. And we feel it most in the cities that are closely tied to global trends in technology, knowledge, and entertainment. Renewal for Austin, like Paris and other cities in the past, requires embracing far-reaching change with new money, new people, and new improvements to the quality of life.

That change must be informed by what the pandemic has exposed: the shortcomings and opportunities placed in focus at “last sight.” Cities will need to move forward admitting their health systems, their broadband infrastructure, and their safety nets do not yet meet the needs of all. Cities have an opportunity to increase their attention to scientific insights and recognize our power as humans promote the capacities for citizens to adapt quickly. Perhaps this moment will also inspire more constructive and effective approaches to managing sustainability, climate change, and wildfire risks.

The history of past greatness must drive far-reaching change. It must inspire new approaches and ideas. Great cities know their stunning “last sight” quickly – and often painfully – becomes the background for a beautiful and creative new world.

Parisians refer to the ever-evolving “spirit” of their city, which transcends the bombings and lockdowns. Austinites might one day say the same.

Editor’s note: This piece is co-authored by Urbanitus co-founder, Jeremi Suri

If you like what you’ve been reading, please click here to subscribe and we will send you updates and our newsletter.

I like the helpful information you provide for your articles.

I will bookmark your weblog and test once more here regularly.

I am moderately sure I’ll learn plenty of new stuff right here!

Good luck for the following!